The Current Location of Dance

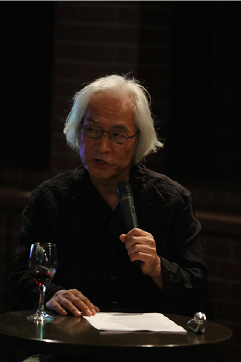

IshiiGood evening, everyone. I’m Tetsuro Ishii. I haven’t seen Ms. Emmanuelle Huynh since before the Covid-19 pandemic, but she tells me she’s actually visited Japan several times recently. She really has deep ties with Japan. I suppose the ties of contemporary dance between France and Japan are stronger than that of any other country. One of the typical figures is Elve Lope, with whom she once collaborated. He created performance art with Japanese dancers at Art Tower Mito’s ACM. I should add Jean-Claude Gallotta to the list as well, who took office as art director at the renowned Shizuoka Performing Arts Center. She stayed in Japan for a long time creating contemporary dance with Japanese dancers, and invited Japanese dancers such as Akira Kasai, Min Tanaka, and Ko Murobushi to CNDC (Angers) where they made collaborative works.

And now you’re here in Japan once again. What’s your main purpose this time?

EmmanuelleGood evening, everyone. My name’s Emmanuelle Huynh. I’m very glad to be here in Japan again.

As Mr. Ishii told you, I visited Japan recently in 2010, 2019, and 2023 for the joint project between the École des Beaux-Arts and the Tokyo University of Arts.

I may have left the National Contemporary Dance Center (CNDC, Angers) about ten years ago, but even now, I’m doing what’s important to me as I did in my CNDC days—that is, making contemporary dance, doing research, and teaching.

These days I’ve been teaching dance performance to architects and visual artists rather than to dancers. I’m also growing interested in how we can learn about the world directly through our own bodies. That’s how my work has evolved so far. For architects and visual artists, as well as for anyone else, it’s very important for them to utilize their own bodies in order to realize the phenomena of the world, though they never do so. The body tells us much of the world. This is very useful for people like architects and visual artists so that they can understand space and the world. I bring architects to this space and create dance with them.

The videos I’m about to show you may give you a glimpse on what’s happened after I left CNDC, Angers, and what I’ve been doing after the pandemic.

ModeratorMs. Huynh will be giving us a presentation with a video she has prepared for us, which will last for about 45 minutes. Sometimes the video may not correspond with her talk, but that is intentional. The video will be showing footage of her recent activities as she talks.

EmmanuelleThe footage starts with “nuage”. Nuage means “cloud” in French. I made it in 2021 after my father, who’s Vietnamese, passed away in 2018. After his death, I went to Vietnam and searched for his footprints. In this work, I compiled my experiences of physical exercise and the feeling of moving my body. It consists of various aspects of bodily sensation and kinesthesia—ballet lessons in my childhood, playing handball, etc.

You can see some text in the background. They are a form of dramaturgy, my answer to the question on what my return to Vietnam means and what I want to express through this. In “nuage”, three French words starting with the letter “P” are used in a wordplay—“pied pas (foot step)”, “papa (father)”, and “pays (country)”. Lighting is a very important factor here, as well as a lot of smoke used on stage, which is a reference to my father’s first name that translates to “Blue Cloud”.

The second video is “lande”. This is a portrait of Houston. I made four portraits of cities with Josephine Coton. The first one is New York (2016), the second Saint-Lazare/Saint-Césaire in France, the third Houston, and the fourth San Paulo.

When I was teaching at an architecture school, I was asked to make a portrait of New York. So I started interviewing those who actually lived there, asking how the landscape of the city affected their body and what they did with their body there.

In Houston, interviewees answered differently or in a different manner, and their visions or ways of viewing things were sometimes contradictory. They—in this video, actually—were asked what Houston was like before it was baptized as Houston (in 1835), and what changes happened after that in addition to the two questions I mentioned earlier.

There I asked three questions to different kinds of people, such as those belonging to the Apache—an indigenous people in America—as well as business people, a storyteller, a geologist, a Spanish curator, a Mexican artist, and so on.

Through these interviews, it became clear—though not quite logically—who owned the land first, and who began to destroy and made profit of it. One specific example was the topic of development and petroleum pollution.

These experiences made architecture and cities a very important theme to me. And through them I became more eager than ever to learn more. I felt it necessary not only to dance, but also to research, especially on things outside of dance. It’s very fascinating to me, seeing the world unfold while using dance as a tool.

IshiiWhile the video continues playing, I’d like to ask you a question before I forget. In the previous video you put stress on your own body and focused on creating your own work. But this one is entirely different; it includes nature, society, culture, and the people’s way of living there. Does this difference signify a change in your philosophy, or is it just another repertoire of your works?

EmmanuelleIt unexpectedly came to me under the conditions given. After I left Angers, I taught dance to architects for the first time at an architecture school. This experience led me to cherish architecture, and now here I am.

IshiiWere there any students in the school who had been acquainted with dance?

EmmanuelleHonestly I don’t know, but I didn’t think it was important. While I was teaching at the school, I went to New York City on a tour of my own work, and someone from the French Embassy asked me to see what I could do as a choreographer with the city of New York as the subject.

It was an opportunity to extend my career and create a bridge for it.

While theater and stage remained important to me, I began to learn about cities.

On the screen is a video of San Paulo. You can see several Japanese people in it. I was so happy for this chance to encounter a city that has many immigrants from Japanese islands. For the “portrait of city” series, we were doing interviews in cities and then making movies. Sometimes we actually performed in a city, and sometimes we took footage of that performance and spread it to other locations.

I mentioned that we’re doing a performance and a creation. What I just showed you was a piece that we produced as a work of art last February at Beaux Arts. Through the creation, visual art students were able to achieve a performance that developed in a different way—more than a technical one, through things like touching and spinning each other.

To add one more word about the “portrait of city” in São Paulo, we did not directly film the city. Rather, our main focus was to document the encounter of 20 artists, 10 students from the Beaux Arts school where I teach, and 10 students from a school in São Paulo. We shared various questions about what it means to be an artist, especially in Brazil today, and what it means to be an artist in situations such as the changing of government or being among a still strong presence of racism.

The work I am showing you now is a recent work that I created in Paris in June of this year. Actually, I was not engaged in this work myself, but was was asked by Benjamin, the former director of the Opera National de Paris, to create it. I did not choose the place myself; Benjamin designated a place called Place Mobert, in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, for me.

This is a place where a Vietnamese community has been established over the past century and where there are many Vietnamese immigrants. He wanted me to not only take the approach that I’ve been taking with my past methodology of connecting architecture and physical movement, but also to incorporate more personal things, personal issues, and materials, like in “nuage” Since I’m half-Vietnamese, he asked me to do in this particular area.

He also wanted me to show what Ho Chi Minh was like when he first came to France in 1911-1913, and from 1929-1933, when Ho Chi Minh came to France again. I had to read and study a lot in order to present this Ho Chi Minh person, this man. How on earth could I show this man, this Ho Chi Minh, whom my family hated? Because He himself is the man who is responsible for causing many people to emigrate from Vietnam.

I belonged to a family that immigrated from South Vietnam in the 1950s. Efforts had to be made to find out Ho Chi Minh was not just a bad man, who was the root of North Vietnam’s rise to communism and who thus played a role in the process of bloody division and unification between North and South with French and American agendas also at work,

What I am showing you now is a work “embracing a tree”. I focused on the tree as a partner, a teacher, and a witness. Just last week we also performed this piece at Villa Kujoyama in Kyoto.

In this work, you see on the screen needles on the floor, on the ground. It’s an acupuncture treatment. It was in 2020 that I started to collaborate with trees, dancing with trees. I visited Vietnam after my father’s death. It was just a very painful experience, because I wanted to go back to how it used to be, but everyone had already passed away and there was nothing left but trees. In this situation, I came across a tree that was 200 years old. This tree must have seen everything. Visualizing the fact that this tree had seen how my own father grew up, or left Vietnam in the 1950s on a boat for Marseille, I started to dance with the tree.

My father was an acupuncturist. He didn’t talk a lot about it. So, I went on to do a geographical cartography of the physical dimension in places like the floor, in trees, and so on. There were a couple of episodes in relation to trees; one was in Vietnam, as I mentioned, and the other was an experience with an olive tree in Italy (which was diseased with a bacteria called Xylella). And the third episode was all the trees I’m dancing in front of; for example, the trees in front of me in Kyoto, where I visited last week—the bamboo groves.

IshiiThe name Ho Chi Minh was mentioned earlier. A great power known as the USA once fought with a small country called North Vietnam, and Ho Chi Minh was the leader of North Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh was a revolutionary in a sense, but there are some aspects other than that. For people like Emmanuelle’s family, who moved to France from Vietnam as immigrants—so in a sense, refugees—Ho Chi Minh was an enemy and a person they hated. But in France, as it was in Japan, the student movement and liberals condemned the US. It was a conclusion induced from opposition to the Vietnam War. Therefore, first of all, I want to know how someone in a position like yours, Emmanuelle, can assimilate such a complex political situation in their mind and then create a piece of work.

EmmanuelleTo answer your question, the work about Ho Chi Minh is a drama, but it is not a drama for me. My father never talked about Vietnam and its history, but wrote down all the details as a book to leave to his child. What that means is my father’s pain was too severe to tell directly. I myself was often asked where I came from, because I look Vietnamese. I would give the name of a place called Renshat Phu and add that I am French. It was a kind of personal pain. But as for the work I just showed, it was not about that. I was devoted to learning about history, and it was very interesting.

My father studied in France. Ho Chi Minh also came to France, but he could not afford to study, so instead he worked in France and became devoted to learning from France how Vietnam could become independent from her—a country that he respected very much. The Vietnam War was conducted in the era of the Cold War when China was a threat to the United States. A small country oppressed by the United States and France overcame these great powers and won its independence. It is very moving to think about how we Vietnamese were able to overthrow them.

QuestionerAs Ho Chi Minh became independent in France, what did he learn there?

EmmanuelleWhen he was in France, there was the Internationale centered on the Communist Party of France. When the meeting of the Internationale was held in the town of Tours in the middle of France, Ho Chi Minh represented the Communist Party of France on decolonization and gave a speech. Through the knowledge and experience he gained from the French Communist Party, he apprehended the way to decolonization. He read a great deal and wrote a lot. His French was also very good, which meant that he learned and was educated during his encounters with people from many different countries.

After making the film, I became a fan of Ho Chi Minh. Above all, I was deeply impressed through the process of following his path, which I felt at the same time was quite astonishing. He met and learned from many people in France, and decades later he became Prime Minister of Vietnam and wrote letters to US Presidents Johnson and Nixon. I came to realize that he was a man who had made those encounters himself. Although Vietnam is still a tragic place, I empathized with his way of life, sometimes taking photographs, sometimes laboring physically in the midst of political activities.

Another episode I would like to add is about my grandmother, who was taken to my father in France when the communists arrived in South Vietnam in 1975. Because there was nowhere else to go, she had no choice. I remember when I was a little girl, I wondered why my grandmother had come to France.

It’s almost time. This space is the place where many of Mr. Murobushi’s books and other materials are in custody. He died too soon. I was in New York in June 2015 when he died. There I received a call from Eiko that Ko had passed away. I really wanted to do something with Ko, but it had become impossible, forever. I have the feeling that Ko is still here, and it’s not just that he’s here, but that he’s here in some other way, in some other situation. It’s a feeling where he’s gone, but he’s still here. I had a lot of students in Angers where I taught, and they all still talk about how much they loved Ko’s way of teaching.

IshiiThe work “Spiel” is on the screen now. It has starkly impressed me. One of the reasons is that the space at Asahi Art Square was fully utilized as many of you might see. You and Kasai-san danced as a duo for a long time with a lot of improvisation, though the general course of the dance was predetermined. You were very focused and it was a very good piece. That’s why. And during this performance, he was speaking. He tends to speak while dancing, and did the same this time. I heard you also were speaking a lot. I’m not sure if you were inspired by him. Quite a few Japanese contemporary dancers tend to speak a lot these days. I can’t say if it’s good or bad, but there are some dancers who speak to cover their dance up even though it’s not really necessary. I would like to know if Kasai-san talked to you about saying whatever you wanted, or if you were required to speak during the performance.

EmmanuelleI started speaking while performing on stage before I met Kasai. I remember that moment clearly. It was in 2001, when I was asked to perform Nijinsky’s “L’après-midi d’un faune” by the group Le Fat Fusse. When I took part in the piece, they asked me and five other dancers to speak while dancing. …… After that experience, I made this performance with him, in which he started shouting, “Wow!” I thought, “Oh, that’s nice. I want to shout too,” and when I did that, despite the difficulty of doing two different things on stage, speaking and dancing, I felt the pleasure from it.

So, dancing with Akira stimulated a very powerful change in my life.

QuestionerHave you actually seen Ko Murobushi perform? I would love to hear any comments you might have.

EmmanuelleHe was a very intense person, and by intense, I mean very focused. I knew him in many different situations: teaching, living, smoking, drinking, and of course, dancing. But I think he had that kind of intensity in all his activities. There wasa work called “quicksilver” for young people. But not only was he always intense, he was also narrow, concentrating on a single, narrow point, going deeper and deeper. That was what his concentration was like.

IshiiFor three days from tomorrow, there will be a workshop by Ms. Emmanuelle at Terpsichore in Nakano. She mentioned how she’s very happy to have her workshop at Terpsichore, saying she knows well that Terpsichore has been a center for Butoh for a long time, so it’s wonderful to have her workshop there. Please come and join.

EmmanuelleWatanabe-san sent me a text related to Ko’s “Faux Pas”. “Faux pas” means to step off the path while walking. From there, I’d like to do something on “falling existence”. It is a metaphor for lying on the floor and connotes getting up again. It is about how we become aware of falling existence and how we stand up. I have already done that in some of my works, so I want to share more of that and do something about falling and getting up.

Infomation

Emmanuelle Huynh was active in a wide range of fields as artistic director at the National Center for Contemporary Dance (CNDC) in Angers. She will be discussing her work and creations after her time as artistic director using video footage. Themes will include her new productions, her encounters with Akira Kasai, Ko Murobushi, and others, France’s reception of Butoh, the influence of American post-modern dance, the current state of French contemporary dance, and the possibilities of Japanese-French workshops. (Tatsuro Ishii)

Date

Wednesday, August 7

19:00 –

Venue

Ko Murobushi Archive Shy

Profile

Tatsuro Ishii

Dance critic. After serving as a Fulbright researcher at the department of drama and as an ACLS researcher at the department of performance research at New York University (NYU), he now teaches as an honorary professor at Keio University. His interests include circus, physical culture with Asian roots, post-modern dance, and performance theory from the perspective of gender and sexuality. Works include “Dance is an Adventure,” “The Critical Point of the Body,” “The Theory of Cross-Dressing,” “Sexuality in Cross-Dressing,” “Polysexual Love,” “Acrobats and Dance,” “Circus Filmology,” “A Darkness with an Aura: the Spirit Journey of Physical Acts,” etc.

Emmanuelle Huynh

Dancer, choreographer, teacher. Working actively with artists from various fields such as sculptors and musicians, Emmanuelle focuses on reconstructing dance from a critical point of view. She has danced for many choreographers such as Dominique Bagouet and Trisha Brown, also collaborating with Hervé Robbe, Odile Duboc, and many others. She has served as artistic director at the National Center for Contemporary Dance (CNDC) in Angers as well as associate artist at Theatre de Nimes from 2018 to 2021, and has been teaching at Beaux-Arts de Paris since September 2016.