Exhibition

Date

28th ‒30th July 2025

Venue

Spitzer in ODEON Theater

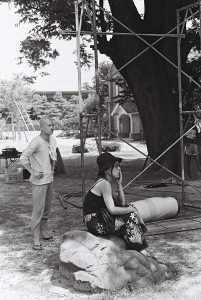

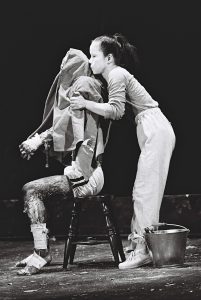

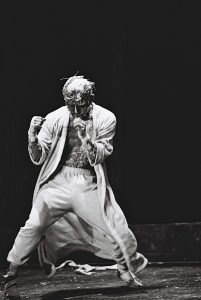

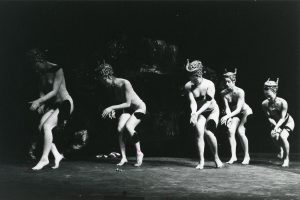

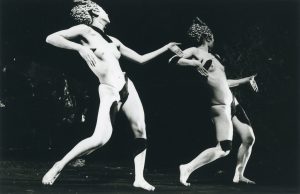

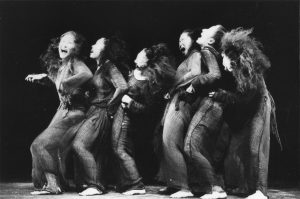

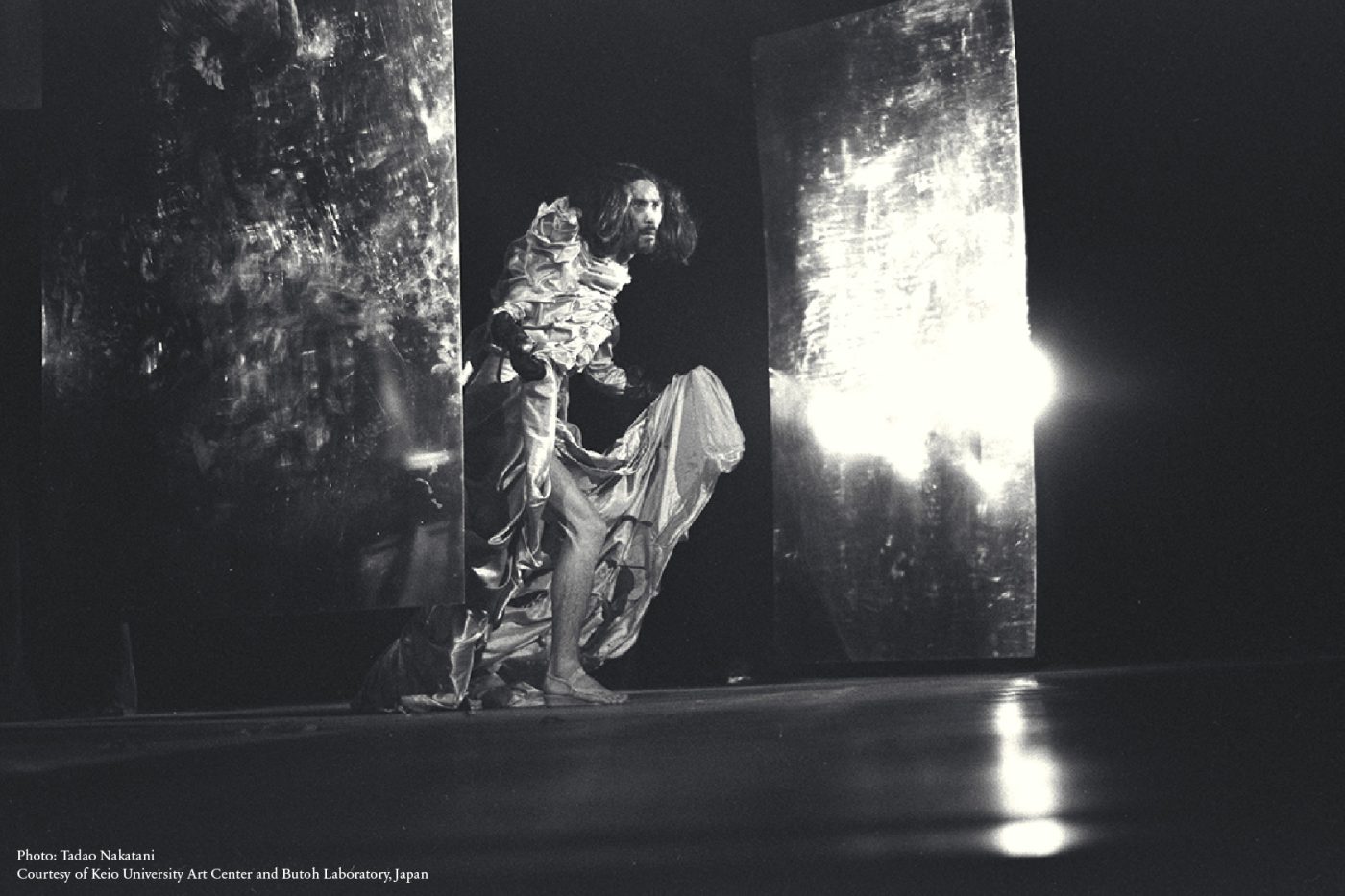

Ko Murobushi (1947-2015) began dancing after he met Tatsumi Hijikata (the founder of butoh dance in 1968, and remained active as a dancer from that point on, both in Japan and abroad. Through photographs, posters, videos and his own writings, the exhibition traces the trajectory of his explorations of dance.

Murobushi’s reflections on dance and on the body cannot be contained within the understanding of “butoh” as a genre: they go far beyond dance theory and practice to ask fundamental questions about the nature of the body and of society. The goal of the exhibition is to offer a reexamination of the field of dance itself, using the traces of dance and thought Murobushi left behind.

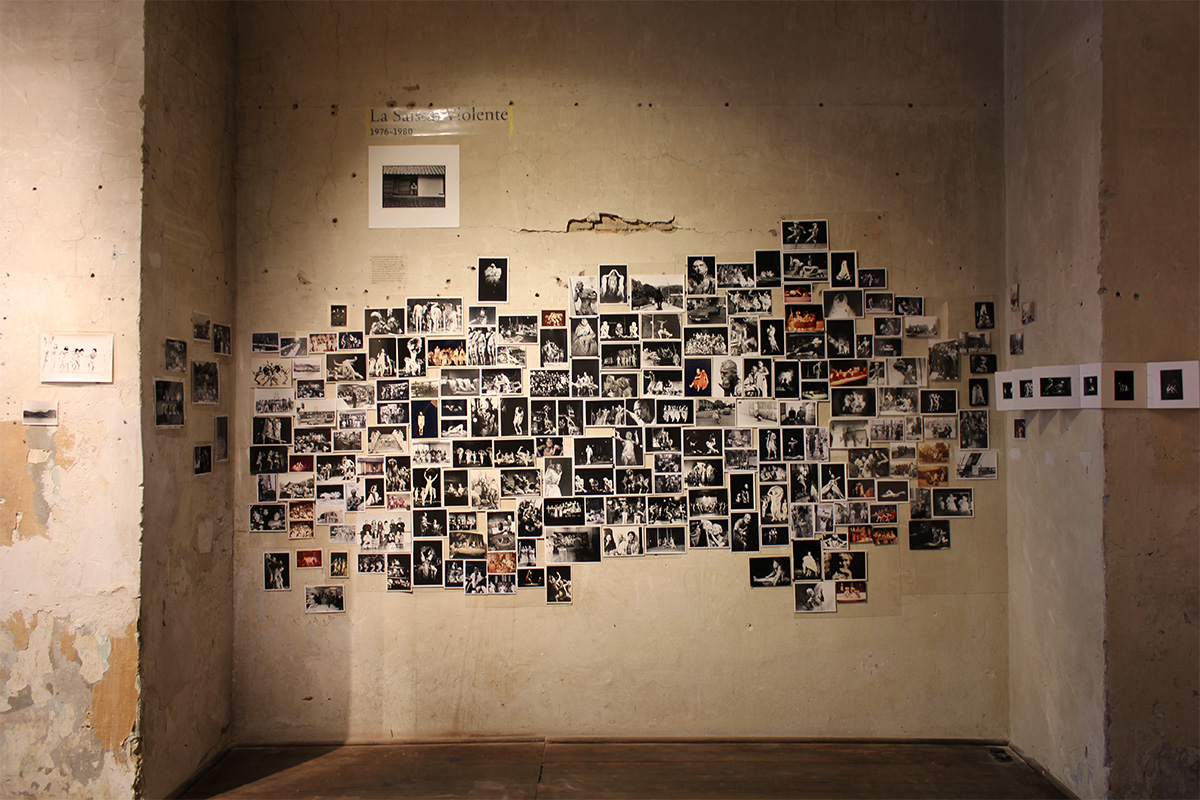

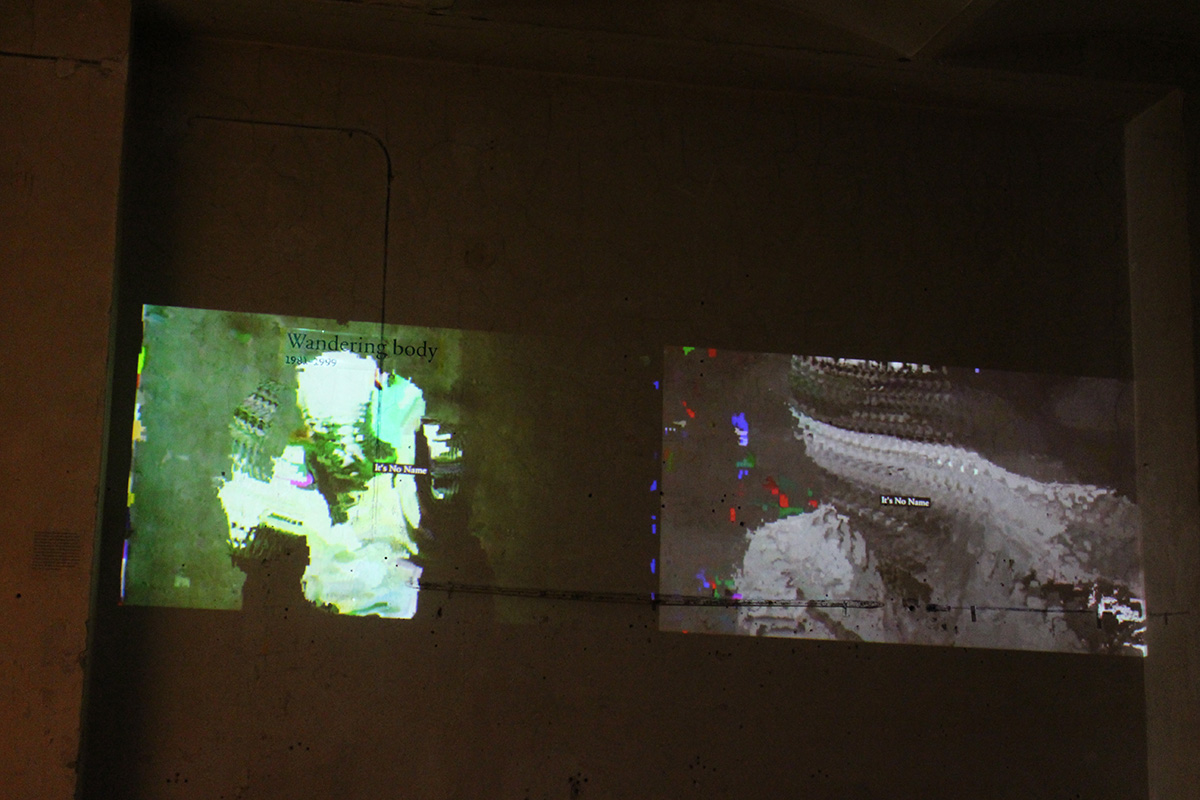

The exhibition covers multiple periods of his career: the early 1970s, and his time with butoh company Dairakudakan, as well as the period after he left that collective to form his own company, Sebi (exhibited in sections respectively titled “La Communauté Inavouable” and “La Saison Violente”); the early 1980s, when he moved to Europe, and gave numerous performances while being constantly on the move (in a section of the exhibition titled “Wandering bodies”); and finally, the 2000s, when he returned to Japan and further deepened his understanding of dance (exhibited in a section titled “Faux Pas”).

Venue

Foyer

Exhibition Details

Rebellion of the Body

Ko Murobushi

Hijikata, playing the prince of the fools, shouted angrily, “Start over!” from within the mosquito net he was being carried in. For a moment, the audience tensed up, as if they themselves had been shouted at. Finally, the procession carrying the prince of fools slowly began to move towards the stage of the Japan Seinenkan Hall. Before encountering the body of Tatsumi Hijikata, I first encountered his “voice,” which split a line between performance and non-performance. It felt like a powerful declaration that the spectacle about to be danced was something meticulously prepared in advance, yet one that would draw its strength from the “one-time contingency.”

And so, Revolt of the Body was performed, and it was a shock. It was a “singular event” resisting description. Or rather, it was impossible to describe because I completely lost my memory of it. I clearly remember the opening scene, in which a naked Hijikata danced while striking the fake phallus he was wearing against a hanging brass plate, but I completely forgot about the other dances that were performed. “The singular event (…) is in the non-form of pure non-event.” If one were to write, “It was a poetic experience,” one should rather write, “It was the experience of the poem.” Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe writes of such an experience—of dizziness that touches the very source of poetry—in Poetry as Experience. I quote him here, for his words touch the core of my own experience and the absence within my memory:

Dizziness can come upon one; it does not simply occur. Or rather, in it, nothing occurs. It is the pure suspension of occurrence: a caesura or a syncope. This is what ‘drawing a blank’ means. What is suspended, arrested, tipping suddenly into strangeness, is the presence of the present (the being-present of the present). And what then occurs without occurring (for it is by definition what cannot occur) is—without being— nothingness, the ‘nothing of being’ (ne-ens). Dizziness is an experience of nothingness, of what is, as Heidegger says, ‘properly’ non-occurrence, nothingness. Nothing in it is ‘lived,’ as in all experience because all experience is the experience of nothingness.

Would it make up for the absence in my memory? But there’s something else. I was struck by the certainty that this experience had already been ‘done,’ even though it wasn’t the case. It wasn’t an experience of déjà vu, but rather the conviction that I already knew, with (not-)my idle body, that such a dance existed, and that Hijikata would dance it in this way. It was this mysterious ‘conviction’ that led me to encounter Tatsumi Hijikata. The following spring, I met Hijikata at Asbestos-kan.

trans. Hanako Takayama

Excerpt from Hijikata Tatsumi—For the 80th Anniversary of His Birth—Fragments

Ko Murobushi

Before I met him on the stage of ‘Rebellion of the Body’, I was looking at two photographs. The name of the mummified Yudono practitioner is Tetsumonkai. That was taken by Naitō Masatoshi. And one from Kamaitachi, of Hijikata Tatsumi running while clutching a baby, taken by Hosoe Eikō. I must have first seen this in a special edition of the magazine Hanashi no tokushū. Between the two photographs was my unmanageable, straying body; and those three bodies were already meeting. Through what? They were meeting in ‘between’, at the section, and what these three, straying bodies, hybridizing at their meeting, were, was the disappearance of the voice. They were an experience of aphasia.

Dance, aphasia. A shout, without sound.

It is a shout, but it is a soundless shout. The voice had disappeared somewhere, and what were the eyes fixed upon? Both eyes were sunken, already rotten. Darkness, the outside of the inside: the two men emerged from there. One runs, rushing through the darkness. The other was sitting, collapsed and doubled over and silently praying. Which to follow?

I was seeing the same thing. In my body I was seeing ‘the same thing’. And so I went to meet both Saint Tetsumonkai and Hijikata Tatsumi.

The motherland that strays to a motherland: that is a foreign country. The motherland: that is the body. The body: that is the thing which is always trembling, it is a wandering on trembling legs. Dance: that is forgetfulness. Remembering in the very middle of forgetting.

Recollection that dances: that falls. Memory that dances: that breaks.

Restoring, repairing, repairing once again: that is the unrepeatable nature of dance.

It is life that repeats one time only; its restoration, repeated.

However, is dance. But, is also dance.

It is life along the way.

There is no dying of dance

Dance is not being able to die, it is not-dying

It is living with death, through death

(In no way does this go so far as killing oneself.

This is because human beings always, after they are too late, kill themselves.)

trans. T.F. Caroe

That which is to Come / Dancing Traces

Takashi Nibuya

The Japanese “dance of darkness” (known as Butoh) that originated with Hijikata Tatsumi shocked the world of modern dance with its strong will to decapitate the historicity of Western dance and render it null and void. It was a rare, true originality born in modern Japan. The western dance world was shocked by the unfathomable “will of the dancing body” that was trying to be anti-historical. However, if we are talking about dance based on the pulse of an ahistorical body, the West had already discovered it in the wildness of the so-called “dance of the savage people,” for example, and Nijinsky’s body had already become his own vitality by introducing that wild physicality into the anemic Western dance. Therefore, if Hijikata Tatsumi’s dance had remained as the will to “erupt from ahistorical folk culture,” then the surprise would not have been so great. If it contained true shock, what was it? I once wrote (in a cheeky and hasty assertion) that if the essence of Butoh were to be limited to the repetition of the ahistorical heartbeat of the body, or to the expression of an “eruption of the folk,” it would soon fall into boring self-repetition, or into an auto intoxicating mannerism, and lose its vitality…and in fact I myself had forgotten what I had written. But one day, when I met Murobushi for the first time, he told me, “Your writing was my imaginary enemy for a long time.” However, with that nostalgic, calm sincerity unique to a Butoh dancer, he continued, “Although it was an imaginary enemy, I read it as the source of my illness that I had to face.” My previous assertion was very clever and assertive, but at the time of my first meeting with Murobushi, the Butoh movement was already in a state of stagnation in reality, with many Butoh companies having essentially disintegrated or fallen into manneristic self-repetition, and in fact one Western commentator even went so far as to say that “Japanese Butoh is already dead,” inadvertently confirming my assertion.

“Western Dance annihilated the body in its will to sublimate the dancing body, resulting in refinement but also in lethargy and anemia.” That is why Tatsumi Hijikata created Butoh as a “rebellion of the body”… However, if the rebellion of the body is left as it is, it will sooner or later subside into a monotonous variation of self-repetition of “intoxication of the flesh” or a refinement of repetition unique to Japan…What should we do? Give Butoh a suitable form and transform it? Like jazz? “I’ve been thinking about it a lot, but even jazz seems to have lost its vitality…” Murobushi continues calmly. His calmness, however, is marked by a hint of strong criticism, and one can sense his conviction that he is trying to find (and has already found, potentially) a “different dancing body” that is neither the body nor the body as an anti-body.

The “dance of darkness” that originated with Hijikata Tatsumi was not simply a rebellion of the flesh against the dancing body. It was shocking in that it was a super-form that contained a new critique of the body itself – a new way of using it. Murobushi Ko was a Butoh dancer who literally continued to fill his entire life with the “center of the possibilities of Butoh.” Murobushi Ko was more than just a new form of Butoh, a constant question, a question of why all bodies have no choice but to exist as dance, or should they be that way – a will to transform the world into “con-media = infinitely floating medium” in the true sense of the word. Murobushi existed as that, not only in his body, but also his thoughts day in and day out. There are traces of the rare, dynamic dance here. Here, in the writing (reading) of this text, it becomes “That which is to come / Dancing Traces.

trans. Eric Selland

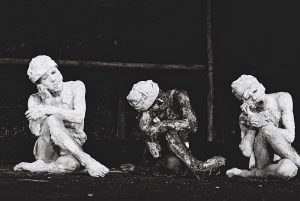

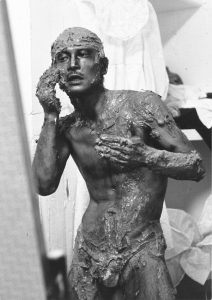

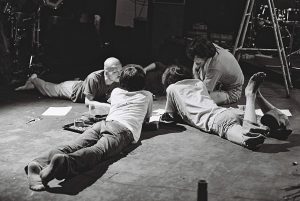

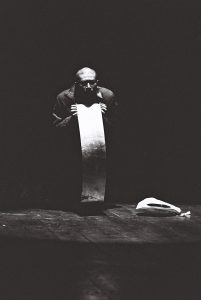

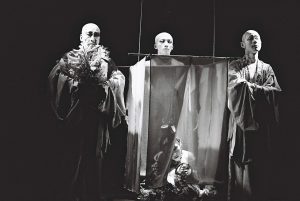

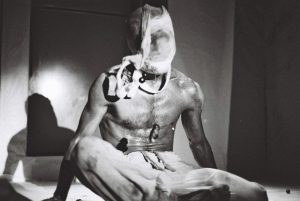

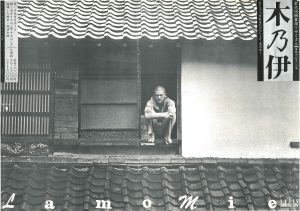

photo

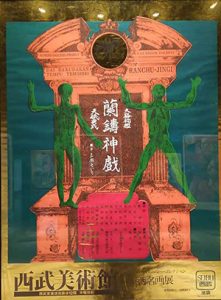

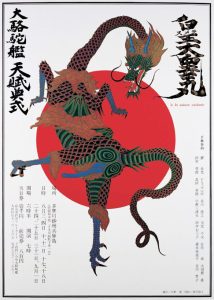

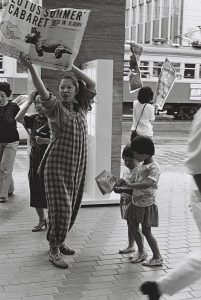

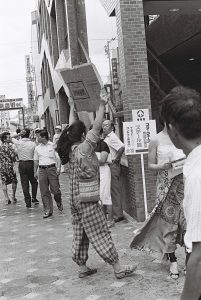

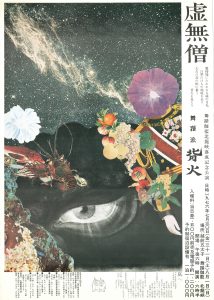

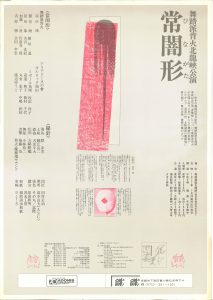

poster

The first dancer was a blacksmith

I write: the first Butoh dancer was a blacksmith.

Our bodies are made of metal – orphaned, exploratory, vagabond, nomadic…

We head north – What draws us to metal… the migration of the migratory bird… will we crash and die? The sky is filled with holes. In an unknown space – a gap or chasm – that which is power = will. It is metaphoric.

Neither water nor earth nor fire nor air. It is a combination of these, a mixture that transcends and deviates from each. This is metal. Its orphan nature. Its disconnectedness. Our muscles and the measure of our nerves, hard and soft at the same time, are light without weight. It’s a heaviness without lightness. This is why we are travelers who can move about anywhere.

I write: the first Butoh dancer was a traveler.

And the traveler – and so the blacksmith, which is to say metal – runs along the fateful line of separation between the collective and nature. The sharp metallic instrument that carves a gash in the soft natural body. The collective, shut out in this way, is left outside. And then we are transported.

The refiring of Butoh begins with the sound of a hammer. It passes through the blast furnace. It is a beginning that has no end – the road to chaos is at once the opening to the cosmos.

I write: the first Butoh dancer was one-eyed, one-legged: and one-armed.

The lame Hephaistos , Alberich the dwarf , the one-eyed Tatara master: the one-eyed jack, heir to Tange Sazen , the one-eyed one-armed swordsman. But rather than being taken up by the illusion/fantasy of restoration of wholeness, this one-eyed one-legged image discards the illusion of the collective, and plays with (fools around with, strays from) this disturbing leg, leg of Butoh, leg of creeping, missing leg, shuffling feet, nomadic and hermetic metallics. In nomadism, only surface matters. Because no matter how rationally sorted and segmented space is, that is to say, interior/exterior, differentiated space in nomadic terms, it is possible to glide over it like a layer of skin stretched and laid out like a sheet of paper. In the nomadic, the interior is a continuum of the exterior. Everything is revealed. … and so…

I write: the first Butoh dancer laid metal on the stage like a piece of skin. A piece of metal separates us as we refuse to possess any technical mastery, experiential memory, or that which is held in the eye.

Yes, this is a theater that has nothing to do with my self after all.

I murmur: yes, I wonder if I ever had a home on this earth.

1992 Paris Ko Murobushi