Nomads who never grow their roots in the ground.

The relation between Ko Murobushi's body and his moving house

Shuhei Hosokawa

In this world, there are people who have been abandoned by the concept of “residence.” They are not, by any means, people with bad intent, and those around them should understand this well enough; however, there are people who just don't have any luck with homes. My friend Ko Murobushi is one of them.

From the time “Last Eden” that started the latest Butoh trend in 1978 in Paris ran at the Carre Silvia-Monfort, Murobushi’s life of going back and forth between Paris and Tokyo began; the only thing that did not go well was having a place to live, or rather, there was a time when the home itself was avoiding him. His residence in Paris these four or five years had been the attic on the sixth floor of an apartment building on Rue de la Gaite, where one could see the Tour Montparnasse and the Montparnasse Cemetery. This room that he had grown used to living in was broken into multiple times the year before last, and unable to bear it, he finally moved out at the end of last year.

He reinforced the lock after the break-in that occurred when he was absent for an extended time due to his Europe tour, but no matter how much he secured it, the lock would be picked; the break-ins were so persistent and thorough that one could even say there was no way but to make it so it would be impossible to enter the room even with the key, and the thieves in Japan cannot even compare. His misfortune with homes is not limited to Paris. Actually, over ten years ago, his apartment had apparently caught fire and various possessions he had up until then were lost (and because of this, amongst his books there are several volumes that are half-burnt). Every time he came back to Tokyo he rented a new apartment; due to the fact that he had to return to Paris after living there for approximately two months, he had a friend live there in his stead, but he did not like this idea and, leaving the arrangements for his next move to his friends, he excitedly made his way to Narita–it is in this manner that he remains without a place to settle.

It was in March this year that I realized these most likely coincidental happenings had an influence on his Butoh itself, when I saw his first Japan performance in five years, “Wandering Body,” at Studio 200 in Ikebukuro.

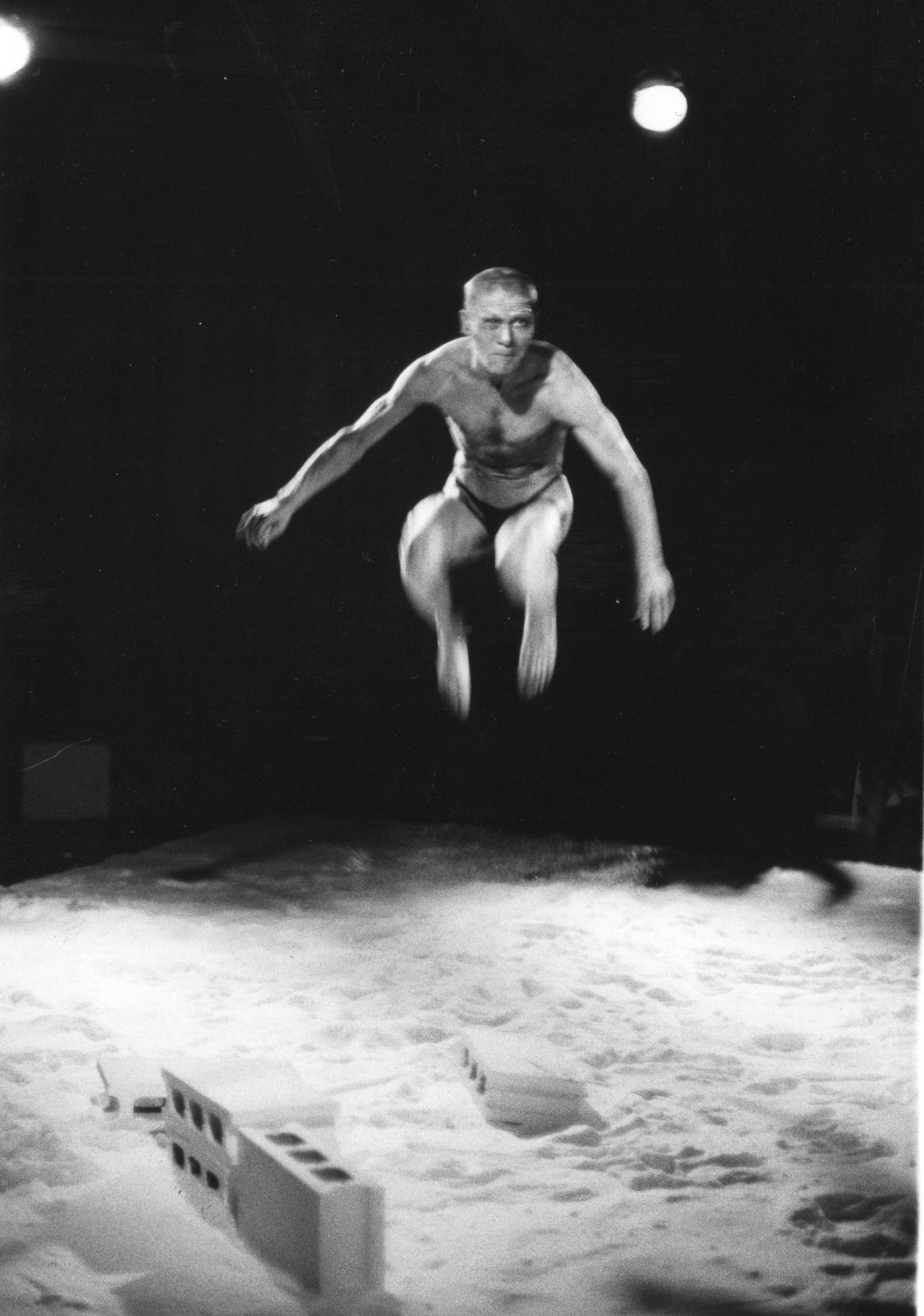

In summary, it was then that I deeply felt he was a nomad that did not grow his roots in the ground. “Nomad” has become the buzzword, and everyone said it with desire and aspiration. But in fact, for a “nomad,” it is simply snatching this and that from various fields and frequenting clubs (the swimming club included) here and there, adding a bit of a “taste of wildness” in expression of the typical yuppie lifestyle. It is but the desire for the outdoor of a long-term resident with a definite home. But Ko Murobushi is a “homeless child” (wandering?) who, beyond having a nomadic lifestyle, is nomadic as a person who expresses the body. With salt spread across the surface of the ground, it was a stage with only a single stool on top of a white carpet. While the color white does not bring Sankaijuku and Byakkosha to mind, it is the basic color of Butoh; however, Murobushi’s “white” excessively stresses the ceremonious nature, and for this reason, the exoticism of foreigners for the Oriental is most certainly not stimulated and, different from the “white” of Sankaijuku, it is white as a substance, the white of salt. The audience that did not know anything at first, too, gradually realizes that it is not sand nor flour, but salt. In other words, this is conveyed through the Butoh artist as he rolls and jumps on top of it, crouching, his eyes becoming red, and appearing to be tinged with a prickling heat. One can even say that it was a performance with a sense of pain. The audience is unconsciously dragged into his physiology and becomes a part of his skin. As much as it is a vector of the dance of darkness’ attachment to the land of Japan and the revival of a racial identity, there was a richness of a concern for the body as an individual. For example, the graceful poses of a beast made by his curving body are not an imitation of any shape, but is the intrinsic rhythm of a beast, the tension when targeting one's prey, and something that expresses a dash in the forest through a single moment in the contraction of muscles. What shines the most beautiful of all is the moment his back is liberated from the demon of gravity, and his skin, like a knife, slices through the atmosphere.

One must think of the word “nomad” as a person who can create an atmosphere where one can feel this tension with the slightest gestures. It is simply an unmoderated form of play; it is not a nod towards a strange watchword called “lightness,” but a title offered to those who can drift about like a strained “presence.”

In regards to Ko Murobushi's personal life, his constant hardship in securing a space (?) is not unrelated to his performance.