Butoh as tradition

Masahiro Kobayashi

I watch the documentary by Director Tomoko Fujiwara, “Densetsu no Maihime Sai Shoki.” This film on Kim Mae-ja, a specialist in contemporary dance and Korean folk dance, following the footsteps of the beautiful dancer Sai Shoki (Choi Seung-hee) who was active in Japan before the war and disappeared in North Korea after the war, is of course a supreme piece of work. However, in addition to that, it is a valuable opportunity to see footage of Sai Shoki’s “dance.” Her “image of bodhisattva” that many Japanese painters and sculptors have made the subject of their work could only be seen as a sensual figure. clothed in a mere amount of cloth adorned with jeweled ornaments and embroidery. It is in this film that you can see the rare footage of the “image of bodhisattva” shot in the United States. Although only her upper body and arms can be seen, Sai Shoki’s dance was something that was neither Western contemporary dance nor Korean folk dance, but something that brought forth movements that were like the personification of something itself rather than the shape.

Sai Shoki was also involved in modern dance under Ishii’s guidance, and of course exhibited her talent in Korean folk dance as well. Sai Shoki is a significant existence when thinking about the theme of “tradition and creation.” At the same time, the somewhat erratic subject of “Butoh and tradition” comes to mind. Although not Butoh, it was from this year that, in Tomoko Mariya’s solo performance “Yaya,” the role of Ryokan that had been played by Matsumoto Koshiro came to be played by Ichikawa Somegoro. It can be said that “Yaya” became a traditional play at this point in time.

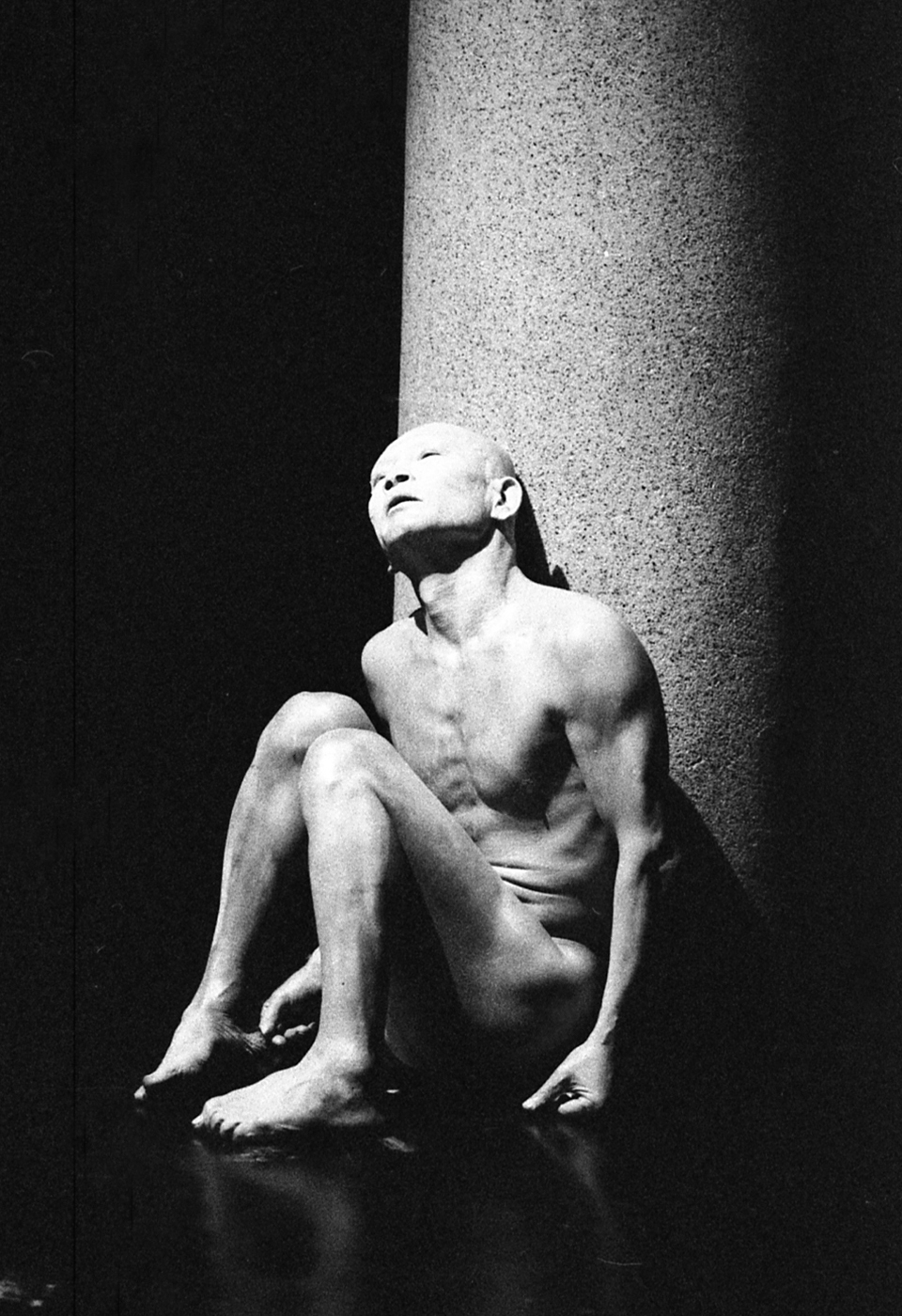

Would this have been possible for Butoh? Unlike kabuki, direct descent is not necessary. Ko Murobushi’s “The People Outside, The Other Things” at Torii Hall on September 12-13 was a work that gave the impression of “Butoh as tradition.” The costumes, stage, and music were all exceedingly simple, with only Murobushi’s pointed limbs. Sometimes moving, falling over, leaping, and crawling. It was a space that, without letting the existence of Murobushi himself be forgotten, made all things conceptual like Butoh and Murobushi’s body into something abstract. Murobushi’s body is not the only thing reducing itself to the minimal. The thoughts of those watching were also being thinned entirely, leaving only a bare amount of the senses. Murobushi’s mentor, Tatsumi Hijikata, once told him, “In your Butoh, I saw a side that was another act without action, of severe idleness.” I think it is exactly that. It is not that something is happening on stage. But certainly, there is a body. Neither an incident nor phenomenon, there is an existence. There is an ontology of Butoh that is inexplicable in phenomenology there. It is neither an imitation nor similarity. However, when I see Ko Murobushi’s Butoh, I can think of Tatsumi Hijikata’s body. Perhaps that is exactly what one can call “tradition.” (omitted)