Porter le préindividuel en pleine nuit–Quelques remarques sur le cahier de Ko Murobushi

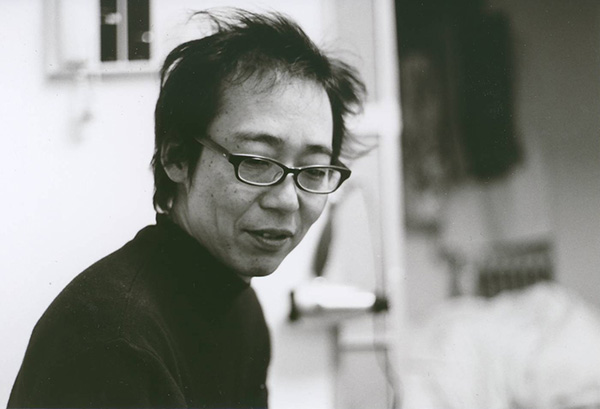

Yoshiharu Shiraishi

Carrying the Pre-Individual at the Dead of Night: Some Remarks on Ko Murobushi’s Note

01

Hello, I am Shiraishi. Nice to meet you.

As the title shows, I would like to talk about what comes to my mind from a point of “carrying the pre-individual (préindividuel)” in reading a text named “Nijinsky at the Dead of Night” (「真夜中のニジンスキー」) which comprises of a spread in Ko Murobushi Collection (『室伏鴻集成』), arranged chronologically during 1975 to 2015.

The concept of the “pre-individual” comes from a book called Individuation in Light of Notions of Form and Information (L’individuation à la Lumière des Notions de Forme et d’Information) written by a French philosopher, Gilbert Simondon. Nowadays, people often mention about a kind of three orders when they talk about environmental problems. They say that the world is made up of a stationary system which includes the earth, life and human being. This kind of understanding has been shared among eco-interested parties recently. However, Simondon had already considered such things in the 1950s.

In the 1950s, ontology was flourished in France. There were Sartre, of course, and Beaufret, who was the French translator of Heidegger. The Roland Barthes was writing critiques of “existentialism” and Camus was still alive. As I remember, it was 1960 when Camus was killed in a car accident. He may have erroneously stepped on the accelerator pedal and brake, but I think he was murdered. In the middle of the Algerian War, the police were said to have killed a great number of Algerians, even in Paris. Nobody can grasp the actual situation still now. Camus’ death in a car accident happened under such circumstances.

Anyway, the 15 years or so between the WWⅡ and the Algerian War were truly a prosperous era in thought. Neither the state nor economy did not put any pressure the public, so that the liberty was possible. In this respect, Japan and France were not so different. The freedom developed in this era started to wane around 1955. Simondon was born in 1924, so he became an adult around the end of the WWⅡ and matured as a philosopher in an age of freedom. As I said earlier, the “existentialism” was flourished at that time. Everyone was talking about “existence.” That was regarded as the only origin of everything. However, Simondon came up with the idea that even the “existence” must have its own origin. Then, he wrote out his doctoral dissertation titled “Individuation in Light of Notions of Form and Information.” It was submitted in 1958. In the thesis, he insisted things like minerals, living things and even the spirit and community of human beings are generated by the crystallization which is caused from a certain kind of an indeterminate precursor. They are all generated through the same pattern and working altogether. That was a large-scale thesis for a free age.

Before the 1980s, doctoral dissertations were required to be published. It seems almost like a fine book written by eminent scholars as their summary of their carrier rather than a thesis since only a few people had written them. Though they had to be published, the writers could publish it whenever they wanted in whatever form they liked. Therefore, Simondon firstly published the appendix of his thesis, On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects (Du Mode d’Existence des Objets Techniques). While leaving some improvements, he separately published the main part in the 60s and 80s, divided into the first half and second. It was not until after his death that Individuation was published in the original form, which we hold in our hands right now. He had been a professor at universities in Paris, however, wrote nothing but Individuation and its appendix. I guess that he himself had been overwhelmed by what he had dealt with.

I would like to repeat that the existence had been presumed as the first principle from post-WWⅡ to the 1950s. In those days, Simondon stopped, thought and raised a question of generation. Then, he boldly developed a cross-sectional concept about minerals, living things, and the spirit and community of human beings, which is referred to as the Earth, lives and human beings today. He named the precursors the “pre-individual” which means a pre-stage of existence, then asserted that things that have been individual, including minerals or living things, “carry the pre-individual.” As I mentioned, this is where today’s title of my talk comes from. Although the description in Individuation is not definitive, one of the main points is that individuation is always incomplete and ends up containing a kind of leftover of the pre-individual. For example, I am an individual – as a substance, living thing and as my whole concept of spirit and community – and I am sure you are, too, but we are not completely individualized. We are not a “unit” (unité) which is supposed to be thoroughly organized. The “pre-individual” as a substratum always follows the individual, and “disparity” (disparate) between them generates another individuation. Individuation is such an inescapable movement of repetition which occurs in the “phase difference” (déphasage). Therefore, the individual is something less than an individual in a relationship with the pre-individual, and it generates something more than an individual which is ahead of another individual. The world is not a collection of individual existences, but the individual movement is throughout it.

02

I had a little chat with Mr. Watanabe, who compiled Collection, a little while ago. Our topic was that Murobushi had been kept writing about “outside” including many texts which were not included in Collection. From 1975 or 77 to around 2015, he had kept saying “outside” repeatedly. Naturally, I had no choice but bearing the “outside” in my mind when I read his book. Now, just to display my ability as a teacher, I can assert that every “outside” in his texts is slightly differs from each other: I should be allowed to give my students a lecture about the differences between this “outside” and that one. This is how I can survive as a teacher. Showing off my ability like that is called “symbolic capital” in sociologist Bourdieu’s term. However, I strongly believe that we should be abandoned such a word from the world. Therefore, I do not want to show my “ability” to compare and verify the “outside” flooded in Murobushi’s text. What we must do is just facing the reality that he mentioned “outside” many times, but not the differences between each word. Mr. Watanabe, who compiled this book, has a correct impression that Murobushi kept saying “outside.” In this very book, Murobushi says that repeating this word is the only way to touch the essence. It tells that repeating is the “outside” itself. This is the point of his story. Besides, the antonym of repetition is probably the representation. It means the “outside” for the repetition is also that for the representation. Murobushi, in fact, appears himself almost naked in his dance, and there, we can find the repetition of the nude. It is not the representation of the nude.

The male nude is common in the 20th century. Before that, it was rare. Looking back on the art history, it is easy to find the male nude of course, but what you see first must be Crist, or probably gods from mythologies. An ordinary man does not show up in naked. When people said nudes, it meant women. Speaking of paintings in the 19th century, one of the most famous arts like “The Luncheon on the Grass” (“Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe”) must be reminded of which men wear clothes and women do not. This situation often gets attention from feminism critiques. However, in fine arts, we notice those nudes are mostly just a symbol whether it is Crist, gods or women, any ways.

At a workshop on the other day, a junior researcher called Rina Suzuki made an excellent presentation about Degas. This painter is said to be a little rebellious. Roughly, many impressionists are anarchy, like Pissarro, he is typical. Their anarchism was political. Being in this group, Degas turns out to be bourgeois. Therefore, he has been easily targeted by feminism. In his female nudes, for instance, he focuses on the process of women’s gesture at the brothel. When it was painted, there was not any proper bathroom, so that a woman uses a metal basin instead. Besides these nudes, he also depicts women in the middle of ballet practice. Those female images by Degas are criticized as a “peeking” from a dominant male point of view. Ms. Suzuki re-criticized this viewpoint. In my words, based on her opinion, Degas did not symbolize nudes.

In the same century as Degas, there is another famous picture, for instance, titled “The Source” (“La Source”). This paint depicts a nude woman holding a pitcher from which water flows. Watching this picture, it is hard to predict what will happen next to her. This is because a certain tradition which had been cultivated in history paintings influenced this picture. The history painting has depicted mythologies and heroes. It needs to capture the defining moment; the coronation of Napoleon is typical. It appears just like a commemorative photo. Every character stands still properly, and their next motion is never implied. Based on such a traditional norm, this woman in nude shows no sign of even a fine move nevertheless the water keeps flowing from a pitcher in her hand. Contrary to “The Source,” repeated movements of nude women are captured in Degas’ paintings. A woman washing her body in a metal basin is a good example. You can guess her following movement. His famous picture of dancers depicts their practices, which is also repetitive, but not their symbolical performances on the stage.

The repetition of nude in Murobushi’s dance can be explained as the same thing as nude women in Degas’ works. The world is composed of repetitive gestures, but not the definitive moments – symbols. These gestures are defined as the repetition of nudes, in the end. Besides, repeating the nudes in this way means to be “outside” of symbolism. Although Degas may have been a little rebellious, as I said before, the symbolism does not occupy nude women in his paintings. Instead, they are the repetition of nudes. It is the impressionism itself that tries to capture the worlds as a series of pointy coloring. There is no room for any authentic characters such as gods or heroes, but only lively colors are painted over and over. When these colors are assembled, the world emerges from their resonance. This idea must be related to the anarchism of the impressionist, the repetition of Murobushi’s nude, and perhaps that of “outside,” too. The nude, which always appears with the repetitive movements against representation shows the “outside.”

03

The things above are, a little too long however, primary remarks for my reading. Then, let me allow to read over Murobushi’s “Nijinsky at the Dead of Night” keeping them in mind. The text starts with a following quote of Huizinga: “ […] the fun of playing, resists all analysis, all logical interpretation.” Johan Huizinga is a historian known for Autumntide of the Middle Ages (Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen). The quotation is from another work titled Homo Ludens. He is now known as a prominent historian, however, interestingly enough, he studied ancient Indian drama when he was a university student.

One young man learns Sanskrit in the Netherlands at the end of the 19th century. I cannot imagine how he felt. Obviously, he could not expect any sound firm position: in fact, he had to settle for an unstable “private lecturer.” His course was on Buddhism. He must be familiar with Nagarjuna and the concept of the “void” and the “nothingness” in his work, The Philosophy of the Middle Way (『中論』). After a while, he luckily got a position at a university, but he was forced to lecture a local history class since nobody was allowed to teach ancient India at that time. This was how he starts his historian carrier. Autumntide is a book which overturns conventional image as the dark middle age. It reveals that on the one hand it was the dark age for the weaken dominant, like the nation or church, but that is the very reason the lives of people were sparkling. Homo Ludens shows a certain vision which supports Autumntide. It says that human nature belongs to “play,” but not to labor. The labor is an exceptional form of “play” which shaped only for the dominant. The reason people in the middle age were so sparkling is that the play as humans’ nature was flooded. This way of conceptualizing play should have its roots in his education of ancient Indian philosophy. It reminds me of Murobushi’s words in the Collection, saying what he was doing can be defined as the east Asian philosophy. This notion is immediately suspended; however, Huizinga came up with the concept of “play” from a “void” and “nothingness” of the ancient Indian philosophy. It is quite natural to link the “void” and “nothingness” as “play” with the repetition of the “outside” in Murobushi’s work, which quotes Huizinga.

I would like to refer to what I said earlier a little more deeply. I said that labor is a limited form of “play.” This type of labor develops civilization. Labor is extracted from “play” based on rules, and by the rules, deviations are controlled. Civilization operates along the chain of “rules – control – labor,” and in this chain, it makes us build more and more gigantic buildings. Such buildings are usually over three stories high. In that situation, it is possible that you die if you fall while you are making it. If you make people build a building with over three stories, it means that you do not care if people die for your sake. Civilization depends on this kind of unbelievable evil. Civilization is dangerous. I think we will wake up from the spell of civilization if everyone lives in a one-story house.

Altogether, civilization always builds huge buildings. The pyramids and the government building in Sumida Ward, Tokyo are the same in that respect. Though you cannot build anything taller than three stories or as tall as the Tokyo Skytree during your playing time, you can build low ones. This is because “play” is something that makes a sideslip. It does not build up. As the word “play” implies, it also means the gap between a certain existence and another. This gap is the very reason why the becoming realizes. The becoming comes from a certain combination of, for example, building materials, of course, but also invisible particles and human encounters. Things and events emerge. Simondon’s concepts of “disparity” and “topological/phase doubling” are also based on the premise of “play” as a void. In the void of “play,” couplings are repeated. We never know what will be combined with what. That is why, as Huizinga’s words, quoted by Murobushi, “the fun of playing, resists all analysis, all logical interpretation.”

To put it another way, there are no gaps in “analysis” or “theoretical interpretation.” If they are full of gaps, it means they are illogical. We can say the same about representations. Representations are based on correspondence, which is inevitable, unlike the combination of “play.” There should not be any gaps in the correspondence. More precisely, a representation is fixed by filling in the gaps, even though it is originally combined by “play” gaps. Under such a regime of representation, the chain of civilization, “rules – control – labor,” operates at the same time. Contrary that, nothing is there even though “play” as a void is a precondition for the becoming of everything, so that it can be said to be the “nothingness” or “void” as Huizinga was aware of. Indeed, right after Murobushi cites Huizinga, he continues that the “play” is the “ultimate waste” and the “ultimate ‘nothingness,’ its joy.” The word “waste” indicates that it is supposed to be unnecessary and should be eliminated from the huge architecture in civilization. Anyway, he says that “play” is joyful “nothingness.” From my point of view, this “play” as the “nothingness” can be corresponded to the repetition of “outside” in Murobushi’s text.

In fact, in “For ‘Innumerable Nijinskies’ ” (「『無数のニジンスキー』のために」), which is collected just before “Nijinsky at the Dead of Night,” Murobushi quotes the words of Foucault that to be “attracted” in the “pure experience of the ‘outside’ ” is to “feel, ‘a state of emptiness and nothingness,’ the presence of the outside and, related to this, yourself who cannot but help be outside of the ‘outside.’” Murobushi, while referring to Foucault, seems to compare his “outside” to “a state of emptiness and nothingness,” which means the gap of “play,” but it should be remarked that his “outside” is turned to be “outside of the ‘outside,’” according to the text of Foucault. The outside is doubled there. If we are to classify the “outside” into the outside 1 and outside 2, I think it is the outside 1 that we usually confront. We can refer to it as enforcement from the outside. We are told that we must do this or that. For example, when I came here today, I thought for a moment that I would enter through the window, but that was not allowed, even if it is very easy and fits my today’s mood. The outside 1 is pervades every corner as the morality of civilization, the enforcement. Against this outside, a symmetrical interiority is constructed. It can be called adaptation to the enforcement of civilization. Things like self-enlightenment and SNS are all examples of adaptations to the external one with the symmetrical interiorities.

In response to this outside 1, the outside 2, the “outside of the ‘outside,’” is supposed. I think, for Murobushi, this is the “play” as the void or nothingness that becomes the world itself. It is indicated as the “ultimate waste,” too, and “ultimate” means extraordinary. Probably, he meant the “ultimate” outside 2, as opposed to the ordinary outside 1. It is called “waste” since it has an asymmetrical relationship to the enforcement of civilization. Rather than symmetrically spinning a narrative of adaptation, it dismisses the very regime of civilizational representation. This reminds me of Deleuze’s definition of “nature” which is cited in a recent book of Takaaki Morinaka, Philosophy of Pure Land Buddhism: Prayer to Amida Buddha, All living things, Great compassion and mercy (『浄土の哲学』). About the “nature,” Deleuze mentions Lucretius’ atomic theory and says that “nature” is not “attributive” (attributive), but “conjunctive” (conjonctive). Being “attributive” means requiring to assign, bond, and be belonging to something. This is the way civilization’s representational regime works. On the other hand, if “nature” is made up of a combination of atoms, then it is the voids between the atoms that work there. It is the “combination” and “conjunction” in the ultimate “play” as the “nothingness.” For Morinaka, the repetition of a prayer to the Buddha evokes the “Pure Land” as this kind of “nature.” For Murobushi, the repetition of the “nothingness” of nudity must have inspired the “outside of the ‘outside’” in the same way. Then, the repetition of a prayer and nudity is a dismissal of the civilization which requires us to belong to labor, and it is also the “pleasure” of the “ultimate waste.”

04

I think we can say the same thing about nudes in Degas’s picture, which I mentioned earlier. Rather than confining the nude female figure to the representational regime of history painting, he invites leads her to the outside of that regime by depicting the repetition of her gestures. Regardless of whether Degas was conscious, there is a “pleasure” of “play” in his nudes, so to speak. Now, I would like to touch a little on women in the 19th century France. At that time, women, not just prostitutes like the ones depicted by Degas, were in a state of “discrimination,” what is now called. Not only did they not have the right to vote, but they also did not have the right to property. This situation continued until the WWⅡ. It was not until after the post-war that women could open bank accounts. In this sense, France in the 19th century was a step backward from the ancien régime that preceded it. In the ancien régime, it did not matter the property rights of ordinary people. Even women could inherit property if their status was high enough. Of course, there must have been some kinds of discrimination against them, but it was never happened that all women in France are treated discriminatory. Contrary to that, France in the 19th century can be depicted as the Taliban. In such a situation, painting women meant painting discrimination. Women appeared not only in paintings but also in novels of the time. There were more and more women in works. All of them were not recognized any right. This kind of setting is not just for The Broken Commandment (『破壊』) by Toson. Those novels have gotten a large readership. The genre called the novel is in which the women with no rights are the main character.

On the other hand, the normal existence was, of course, men for the Taliban-like France of the 19th century. It means a “man” (homme) is “humans” (homme). Finally, in the 20th century, post-humanism was brought up for discussion. Perhaps, the image of “humans = man” will be washed away like a drawing on a beach. Even so, “AI” will not replace “humans = man” as is vaguely believed. Let’s recall Simondon. We know an individual is individuated = becomes into another individual through the “disparity” or “topological doubling” with the “pre-individual” that it carries with. Then, what is the “pre-individual” for “humans = man”? At least, in case of France, it is “people” The French Revolution began with a sudden rebellion of “people” There were no boundaries between men and women, or adults and children. We can read signs of such a condition in “The Marriage of Figaro” (“Le marriage de Figaro”), which was performed the year before the revolution. In the ancien régime, “people” are not so much incorporated into the representative regime of civilization. They were in a state of “nature,” as Deleuze referred. “people” have no reason to “belong,” but only repeat the “combination” and “conjunction.” It was not “humans” who rose in rebellion, nor could it be said to be anyone. The rebellion of “people” crystallizes through the void of “nothingness” or “play.”

Roughly, the French Revolution, from the storming of the Bastille to Napoleon’s rule, is a process of gentrifying “people.” In “The Marriage of Figaro,” “people” are seemed to be fun, however, the revolted “people” must have been a terror to the bourgeoisie of the time. As the first step to gentrify them, women are subtracted from “people” As I mentioned already, women in general were placed in a state of discrimination. The so-called “human rights” (les droits de l’homme) are the rights of “humans = man” (homme). And “citizens” (citoyen) covered the abstraction of “humans = man” up. By doing so, it is possible to gentrify “people” who may lurk in the countryside. The reason male philosophers of the time often talked about “humans” and “citizens” is because they rode with the gentrification of “people” From Kant to Comte, with Hegel in between, the concepts of “(hu) man” and “citizen” were polished. They must have been afraid of “people” since it is a “game” of “nothingness” after all. Murobushi’s dance is also a sort of something eerie…

Of course, the 19th century France was not all about the Taliban thing. We have nudes by Degas and novels in which women are main character. Besides that, we also have “The Afternoon of the Faun” (“L’Après-Midi d’un Faune”) which appears in “Nijinsky at the Dead of Night.” As Murobushi also mentions mountains and mountain priests, a faun is like a mountain kami. You could say they are like Dionysus. They invoke the “nature” of the mountains against the civilization of the plains. In “humans” and “citizens,” he invokes “people” the pre-individual. This is the theme of “Afternoon of a Faun.” In fact, quoting Huizinga again, Murobushi says: “The hybridity in between, the multiple encounters in combinations, the innumerable differences and their changes of the becoming – these are the first principles.” The same can be said about “people” appeared in “The Marriage of Figaro” and the rebel of the French Revolution. Dance may have been “play” as a repetition of “nothingness” for Murobushi, but it may also have been an attempt to evoke the “outside of the outside” of “nature” that he himself was supposed to be carrying, in other words, “people” as the “pre-individual.”

Grounded on those things, I would like to read the last paragraph of “Nijinsky at the Dead of Night.” He starts his writing by saying that “[t]he art is use of uselessness.” The phrase “use of uselessness” must be quoted from Zhuang Zhou, but it is so complicated to explain that I skip it today. Then, he continues “a game = almost play. Unproductiveness contraries to productiveness, play contraries to labor, a festival = a ceremonial ritual = to go wild = going into the mountain without returning = ‘living the death’ = then, to contribute to another, prospective ‘sex = life = production.’ Play, it is something being completed = becoming through and with the body.” Here, the “play” is “unproductive” thing against “labor.” “A festival” and “mountains” are reminded based on “nothingness,” rather than “uselessness.” Perhaps, the “combination” or “conjunction” will happen at the criticality of civilization. It means “living the death.” We would like to recognize the idea of “living the death” as the outside of the outside which shows a way to the “pre-individual.” This is because there is no “another, prospective ‘sex = life = production’” without “disparity” between the “pre-individual” and us. Moreover, this kind of “play” is impossible without “body.” It is our “body” that means the outside of the outside and carries the “pre-individual,” “people.” Taking a form of “being completed = becoming,” “combination” and “conjunction” happen over and over.

This repetition of the “body” as being outside of the outside occurs in the “play” of nothing at “the dead of night,” so called. Schematically, daytime is a world of representation. On the other hand, if the opposite of representation is repetition, then night must be a world of repetition. Come to think about it, most of what we do at night is repetitive: things like brushing your teeth or breathing in your sleep. The “night” in which the “body” repeats itself reminds me of Society Against the State (La Société contre l’État) by Pierre Clastres. He was an anthropologist who devotedly investigated ethnic minorities who were oppressed by the military regime in Paraguay in the 1970s. He also died in a traffic accident, like Camus, in 1977. Not so long before that, his mentor, who was doing the same research, also died. It seems a little strange to see them dead one after another. Anyway, in Society Against the State, Clastres explains that the state or civilization does not leave behind uncivilized people but live in a state where they have escaped from the enforcement. Nations and civilizations are always hand in hand with hierarchy. In contrast, in an uncivilized society, equality is always the priority. It means their leaders are in an unstable position. This is the way how they are protesting the state and civilization. This kind of interpretation may be one of the most major ones in reading Society Against the State, but what I found interesting is that in the uncivilized society as the outside of the state and civilization, another outside is found. Even uncivilized societies have their rules such as “no bragging” and “no monopoly of your hunting fruits.” Although these are their own rules, it is still troublesome. So that they sing alone at night being tired of such rules. They sing a song of night. It is not much of a song. Their song is, for example, about his hunting skill which he claims the best in the world. This concept is paraphrased as “‘The Afternoon of a Faun’ (masturbating)” in “Nijinsky at the Dead of Night.” What is important, anyway, is that this action is the outside of an uncivilized society. First, there is an uncivilized society which is the outside of the state and civilization. Then, the song of the night is sung as the outside of the outside. According to Clastres’ beautiful text, this is the state of “I sing; therefore, I am,” and “they awaken to the universal dream, the dream of going beyond the self as it is.” We can see that the outside of the outside is evoked by the individualization through the song at night.

There is a famous book by Jordania called Why Do People Sing? Also, there is another book On the Singing Origin of Language (『さえずり言語起源論』) by Okanoya Kazuo, who contributes a commentary to the book in translation. Reading those books, you see that singing is a way of holding one’s breath. Birds can sing because they need to hold their breath when they fly. Whales can also sing because they will drink water if they can’t hold their breath. Among primates, for some unknown reason, only human beings can hold their breath. Therefore, they can sing. As they hold their breath, a gap or “play” arises. Nothingness is there. They sing by interrupting the cries. Originally, they were used to chasing away lions and other animals, which must have been dangerous for them. Having sang in groups, lions may have backed away, just like cats. In this respect, the song and dance must have been linked. The important thing is that, at the root of the song, you can notice the physicality which is next to death is appeared as holding one’s breath. I think that the generation of words with this void in them is probably what we call poetry. Song, dance, and poetry are all based on the physicality of holding one’s breath. They are based on “play” as a void, a repetition of nothingness. I think the reason individualization occurs outside of the night song is because we are holding our breath, or to use Murobushi’s words, “living the death.” And I think that only the repetition of such gestures can evoke some futurities through the “pre-individual” called “people” that we carry to the outside of the outside.

05

In 2011, there were explosions at a nuclear power plant, and now we are in a COVID-19 disaster. Under such circumstances, what is the significance of reading Collection published in 2018? At least, as “Nijinsky at the Dead of Night” tells us, we should reconsider the world itself based on the repetition of physicality as “play” or “nothingness,” as the outside of the outside that can only exist at “the dead of night.” I think this is what we should read from Murobushi’s text. Globalization of today means encompassing the world under a regime of representation. This may be true even if we consider it within the framework of latter-day. The same can be said for longer life civilizations. In such a regime of representation, the radioactive substance was scattered, and the highly lethal virus is swept. Both cannot be represented. Even though they surely exist, they deviate from the regime of representation. What is being questioned is the externalism or body theory for invisibility. As well as Deleuze’s theory of Lucretius, Murobushi’s “play” and the repetition towards the outside of the outside can also be said to be the spirit of the same body theory for indivisibility. The world is not controlled under visibility without gaps. It has countless invisible voids. The physicality is repeated in the song at night.

Last, I would like to add something about the history of philosophy. Lucretius talks about the atomic theory. But it has nothing to do with atomism as a metaphor for the isolated individual, as it is referred to sociology in the 19th century. Myths justify the origin of civilization by talking about gods. The counter-discourse to this is a so-called natural philosophy. The origin is not the gods, but water, air, or something “limitless.” This discourse goes as much as saying that everything is in flux, in becoming, in motion, and not fixed gods. On the other hand, Parmenides and Zeno, denying generation and motion, consider not gods, but immobile beings, as the origin of the world. They deny the becoming and motion. Arrows do not fly, and Achilles cannot keep up with the turtle. The atomic theory resolves this kind of conflict between the becoming and existence. It talks about becoming as a combination of the existence of atoms. Consequently, natural philosophy is concluded with the atomic theory, however, a certain problem arises. The problem is that the gaps between the atoms. It is the problem of nothingness. Plato and Aristotle tried to fill in the gaps with ideas and forms. They asserted it does not mean there is nothing, but there is spirit. From this point of view, they constructed a regime of representation. The “play” that Murobushi speaks of is something rejecting their way of filling of voids by the spirit. There are countless voids in the world. We see physicality, not spirit, in them. We see the repetition of voids. Where there is nothing, we hold our breath. We become the living dead. From this nothingness, the voice is generated. Dance emerges. The world comprises such repetition of gestures.

Perhaps Simondon also thought that the world is made up of repetitions of such voids or “disparity.” In this sense, I think the “pre-individual” is also called “play” that is not fit neatly into the representation of the individual. The world pours out from such “pre-individual” as “play.” The world is not a shadow of idea, and it does not fit into a mold of form. In the wake of the COVID-19 disaster and the accident of nuclear power plant, we are at a loss what to do unless we seriously consider the physicality of the invisible that functions in the countless voids that have been created. That is why we have to read Murobushi’s texts over and over. In fact, for Murobushi, the body is the energy itself that works in the formless void. The following is the last part of “Nijinsky at the Dead of Night.” “The body = the movement of the sincerity of power. The sincerity is infectious. Ephemeral, unstable (hakanai). Hakanai evokes “without” (nai) and “tomb” (haka). In think that the “tomb” is a symbol of civilization. If you make it bigger and bigger, it becomes a building. “My own body is a tomb. Thus, to find the minimum and maximum significance of what is possible in the combination = hybrid of significance and non-significance, of meaning and meaninglessness… To invent, to discover/be discovered. To be the “becoming-event-between.” “Hybridization” is “play” of nothingness, the combinations that happen outside of the outside. In the repetition of such “hybridization,” “people” as “event” is coming. Do not be humans. Become “people” through the “pre-individual.” That is what I would like to say. Thank you for your attention.

Yoshiharu Shiraishi

Born in 1961. French literature. Part-time lecturer at Sophia University and others. Introduction to Criticism of Modern Life in Neo Ribe (Shinhyoron), Impurity Liberal Arts (Seidosha), etc.