The Nijinsky Incident

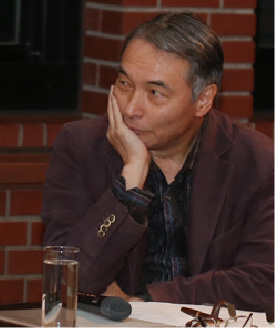

Kuniichi Uno

Everything that the heart feels is reason

– Vaslav Nijinski[*1]

01

Suppose there was such a thing as the Nijinsky Incident. In the course of his emergence and demise, the greatest dancer of the century’s path crossed with two World Wars and the Russian Revolution. The dancer vanished after his dance was snatched away by madness. Without ever appearing on stage again, the only leaps captured in film were the ones he made in his last days at the psychiatric hospital. However, that incident itself is made up of a chain of countless events. By the time the incident turned into legend, thus making Nijinsky the name of the incident, the course of events had already been absorbed into that name, hidden, eradicated, and made invisible. A dance prodigy of madness. His miraculous leaps. The scandal of The Afternoon of a Faun. His demise. His mythology. If it was not for his glorious emergence, there would not have been his tragic demise. However, if all these events, everything he went through, cannot be encompassed by such a mythological word as “fate,” then these things can be considered no less than a life chosen out of the solid volition of the individual. Despite the uncertainty of what actually happened, the legend was created. There is no knowing what actually turned into myth and legend anymore. What really happened? Anything? Though it seems nothing has happened, perhaps something extremely important has.

Soon after the appearance of his symptoms, Nijinsky made entries in a diary intensively for about 40 days (January 19th-March 3rd, 1919). It seemed as though he volitionally tried to address the questions of why and how he became a dancer and how much of a success or setback his dance had been through The Diary (The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky). He writes that he even took up madness by pretending to be mad.[*2] Besides, everything that happened to him seems to be a divine trial which progressed while in dialogue with God. The main theme of The Diary is to affirm feeling, criticize intellect, and confirm the union of reason and feeling. For Nijinsky, “Everything the heart feels is reason.”[*3] And perhaps the other major challenge is to understand death. (“I think of death because I do not want to die.”)[*4] Though love and sex are indeed the major questions to be posed in the realm of feeling, love and sex are always in a conflicted relationship.

These questions must have been tearing Nijinsky’s psyche to pieces. What remains a mystery, however, is why Nijinsky fell into madness (likely a typical schizophrenia), because psyches that are torn to pieces do not necessarily present such symptoms. The only thing the readers of The Diary can do is merely guess what life his psyche lived and how. Naturally, there are numerous ways to interpret what is written in The Diary.

One is to read it as a record of pathography (as though conducting a psychiatric examination). Of course, this cannot be the way Nijinsky would have intended it to be read. One might be able to draw some insights from psychopathology and psychoanalysis, yet they do not essentially elucidate Nijinsky’s mentality, his madness, or who he was. Words in The Diary could certainly provide us with clues to deciphering his pathography. However, Nijinsky, who was suffering from and battling with his illness, refused to be analyzed as an object, one merely affected by an illness, as long as he remained a subject that lived in a state of unusually strong tension. Reading The Diary as a case study is already an interpretation that has been artificially constructed. However, Nijinsky was certainly both conscious of his symptoms and fighting against them, thus trying to recover and rebuild his psyche. (Michel Foucault once stated that a symptom itself is one of the expressions of resistance against etiology.)[*5] Therefore, another way to interpret The Diary is to simply read it as a record of the psyche of an individual without assessing whether that individual was sane or insane. In other words, it is to read, with a completely impartial mind, what Nijinsky intended to record and convey, while following the footsteps of his conflicts and confrontations. That should be one of the many ways to read it, but in fact there is no way one’s mind can be impartial. Just as Nijinsky’s thoughts were torn apart, so too the thoughts of those who read The Diary have no choice but to be torn apart and shaken.

God commanded me.[*6] Everything is as God desired it to be. Such ideas are powerful motifs that drive The Diary as a whole. It’s not that I am manipulated by God. God resides within me, he writes.

In his last dance where he confessed that he was going to marry God, Nijinsky allegedly declared, I’m going to dance the dance of war. One might say The Diary that he started to write on that day (January 19th, 1919) was waging a tremendous, wide-ranging battle. There were countless enemies to fight against: the rich, the aristocracy, Diaghilev, critics, cannibals, stock exchanges, politics, wars, Loyd=George, Bolsheviks, his wife’s family members, and more. But enemies have the ambivalence of occasionally becoming allies. The writer constantly insisted that he was recording nothing but the truth. Surely whether that truth was illusory or factual no longer matters. Whether the battle was an illusion or a fact, the diary is a record of what a single soul has lived and, if not lived, what has been intellectualized. All the words Nijinsky wrote were written as a battle, a conversation with himself, a dialogue, a declaration, a calling, and a scream, and thus can only be interpreted as what they are. Though we find ourselves having a difficult time deciding from which point of view we should comprehend it, Nijinsky, too, was under such a circumstance, one where he was torn apart and shaken as he thought and wrote.

Nevertheless, it is necessary to review what sort of expression, what sort of occurrence Nijinsky’s ballet was. Ko Murobushi did not show particular interest in Nijinsky’s dance itself, not in its technical aspects, how it was staged and choreographed, nor did he aim to recreate it or make it the subject matter of his own dance. However, when he envisaged Nijinski à minuit, he certainly took basic features of Nijinsky’s ballet into consideration. He jotted down the following lines.

Dance is deviating further and further from the power it inherently owned.

The point when the dance is abandoned is, in fact, where the power that spawned it resides.How close, and in what way can we get to the origin of that fundamental power?

What was there in the origin of the power?There might have been a Faun, a Sphinx, or a Phoenix.

Nijinsky’s The Afternoon of a Faun was born of the innate energy to question from where the human fetus emerged.

A being that exists between human and beast,

That which is considered a horn as well as a fang

That which has lost the words of a human,

That which has lost the love of a human[*7]

Even if Nijinsky’s legendary leap was extraordinarily impressive, how high or far he leaped, let alone his physical capabilities, were not of major concern. What should matter is the fact that the leap itself was entirely a form of dance. Bronislava’s description of her brother Nijinsky gives a vibrant and fundamental account of what his moves were like.

One of the astounding features of Nijinsky’s dance was that it was impossible to tell when he had completed a pas and moved on to the next one. Preparations were made in the shortest time possible, that is to say, everything was hidden at the moment his feet touched the stage floor. While entrechat six, entrechat huit, and entrechat dix are repeated obsessively in the background, every conceivable movement, including vibrating, trembling, flapping, and soaring was occurring in his body. After each entrechat Nijinsky didn’t come back to earth, but instead, like a bird, seemed to be flying ever upwards. All entrechat melted into the ascendant flight, thus forming a continuous glissando. There was something magical added to the imagery of a bluebird dancing (in Sleeping Beauty.) [ … ] Arms that displayed dynamic movements, or wings, in other words, opened when you thought they had closed, and it was as if they were making him float in the air, within an atmosphere, an element all his own.[*8]

In opposition to norms of classical aesthetics like forms, poses, rhythm, geometry, and symmetry, strange movements with strange principles are unfolding here. These movements are not a heteronomous composition but instead a formless, unconfined flow which resides “within an atmosphere, an element all his own.” It is nothing more than autonomous creation, an undividable continuity, a sequential change (glissando). Of course, highly skilled movements (virtuoso performance) in any dance often must have this aspect, but it is broadly a secondary decorative aspect that follows a normative aesthetic. However, in contrast, Nijinsky seemed to have envisioned a dance whose principle was this kind of glissando. Nijinsky keenly perceived autonomous modulation of colors in painting (which is in opposition to color laws that are subordinate to the demands of representation such as color value), and sequential changes in music where the sound itself becomes a kind of materialistic process, breaking out of formulas of scales and tonality. He was in pursuit of movement which corresponded to each of these perceptions. It seems he inferred aesthetic transformations of the age to be inevitable and necessary shifts, and strived to discover and refine techniques which accommodated them.

Another revolutionary thing was that in The Afternoon of a Faun especially, Nijinsky realized a composition where gestures were mosaically arranged: He denied the classical movement of ballet itself, decomposed it, and slowed it down, piecing together poses in a certain flatness like ancient Egyptian reliefs. In other words, Nijinsky deconstructed and deformed ballet’s three-dimensional organic movements as if making them inorganic, while also reducing them to two dimensions.

Michael Fokine commented on Nijinsky’s dance in Scheherazade.

He was lacking manliness […] and perfect for the role of a slave. He looked like a primal barbarian. It was not because of the body makeup but his movements. At one moment he would make a big leap without making any sounds as if he became a half-human and half-feline beast, and the next he would become a stallion, nostrils flaring, energy overflowing from his entire body, fiercely stomping around the stage as if he had hooves.[*9]

The bestial nature and wildness Nikinsky rendered was aligned with the exoticism and orientalism that the Ballets Russes embodied in Paris. To get a sense of it, just imagine, for example, what kind of inspiration and transformation was brought to Western modern art by African sculptures and masks, and Japanese ukiyo-e.

Additionally, the flatness, the inorganic quality, and the mosaic of fragmented gestures eventually departed from what ballet was and converged with gentle, unorthodox gestures in the last scene of The Afternoon of a Faun. Auguste Rodin commented,

There were no longer leaps or displays of virtuosity. There were only gestures and movements of a beast half-awakened to human consciousness. He would stand up, bend over, kneel down, hunch over, and suddenly stretch out his body. Sometimes slowly, and other times abruptly, he would tensely and awkwardly move forward and scoot back. His eyes would search for prey, his chest spread wide, his hands would open, then close while his head wobbled, tilted, and arched backward. Every part of his body expressed the movements that passed through his mind.[*10]

In this way, Nijinsky realized a dance with gestures that seemed to intimately correspond to the weight and density of flesh itself rather than the spirit of romanticism.

02

In Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Deleuze and Guattari quote The Diary as the only document of the Nijinsky Incident.

In Le Baphomet Klossowski contrasts God as the master of the exclusions and restrictions that derive from the disjunctive syllogism, with an antichrist who is the prince of modifications, determining instead the passage of a subject through all possible predicates. I am God I am not God, I am God I am Man: it is not a matter of a synthesis that would go beyond the negative disjunctions of the derived reality, in an original reality of Man-God, but rather of an inclusive disjunction that carries out the synthesis itself in drifting from one term to another and following the distance between terms.[*11]

To summarize, the three notable logics in The Diary are as follows.

1) I bellow, but I am not a bull. I bellow, but a bull that is killed does not bellow. I am God in Bull. I am Apis.* I am an Egyptian. I am an Indian. I am a Red Indian. I am a Negro. I am a Chinese. I am a Japanese. I am a foreigner and a stranger. I am a seabird. I am a land bird. I am Tolstoy’s tree. I am Tolstoy’s roots. Tolstoy is mine. I am his. (*In ancient Egyptian religion, Apis was the sacred bull of Memphis, thought to be an incarnation of Osiris or Ptah.)[*12]

It is precisely this part which operates in the logic of the passage of predicates which states, I am A, I am B, I am C, …

2) “I am not a bull. I am a bull.” He pursues the inclusive disjunction of I am A and I am not A. Rather, it is about becoming-A. It is not that he is a Faun, nor that he is not a Faun, he is a becoming-Faun. It is about a becoming-madman. This disjunction, which is also the logic of becoming, leads words to another dimension where the law of the excluded middle does not exist. That is not chaos at all. It is necessary to create another dimension of language in order to be A and not be A at the same time.

3) Finally, “I write I am a bull.” He is always firmly aware that he is writing. Through the words written in The Diary, another dimension of language was created. He was no longer writing to argue a proposition (the judgment of true and false). “…I want to speak all languages. I cannot speak all languages, and therefore I write”.[*13] “I write I am …” In this way, Nijinsky invented a new horizon of language that was equipped with a totally different usage (grammar). At the same time, it was a language that was meant to carefully measure and figure out if he was crazy or not. (In other words, it is a scale for Nijinsky’s nerves.) Through writing, Nijinsky coped with psychological dilemmas, breaking out from the exclusive disjunction that divides the affirmation and negation of love, true and false, and justice and evil. His trials and struggles continued for this purpose, and the dimension of language and thoughts was dismantled while another dimension was created.

In the first edition of The Diary, outright sexual remarks, slander towards other people, and poetry written in fairly simple vocabulary were mostly omitted due to his wife Romola’s concerns. It goes without saying that the part where Nijinsky bought a prostitute was also deleted. He wrote about his boyhood as a promising student of a ballet school, and as a rich baron’s lover. Nijinsky also mentioned that encountering Diaghilev, his next lover, eventually determined his fate. It seems that prostitution is one of the obsessive main themes in Nijinsky’s Diary. He writes, “I am god’s instrument…I love rich men,”[*14] “I disliked Diaghilev, but I lived with him,”[*15] and “Diaghilev has harmed not you but me.”[*16] In exchange for his body and his talent in dance, Nijinsky ended up acquiring art, wealth, and glory. However, he would never have become complete as an artist, as a human, or have perfected love without leaving Diaghilev, thus becoming independent. One can imagine that Nijinsky had thoroughly investigated his own sexual and artistic circumstances to this point. He was trapped in multiple double-bind situations that overlapped with each other (love’s ideal vs sexual guilt, being a free person vs being a subject, and success vs failure). Did he attempt to get out of that state by abruptly getting married to Romola (thus, perfecting love)? In the end, he was fired from the ballet company, which ultimately led to his downfall as a dancer. While this series of events could be an important clue for pursuing pathography (or psychoanalysis), perhaps the issue of exchange was at the center of the conflict that tormented Nijinsky.

Capitalistic exchange goes far beyond the dimension of an equivalent exchange of labor and money, and extends to sexual, physical, and aesthetic dimensions. Prostitution is not just an exceptional and marginal exchange. As Marx claimed, labor that produces outcome or artworks (oeuvre) and turns it into value, by itself, increases the devaluation (dépréciation) of the doer.[*17] Body, charm, and beauty are living currency[*18] as well as universal commodities that are interchangeable with all things. Aesthetic, artistic, and poetic values can also be the subject of exchange and trade, ceaselessly urging the creation of values and disrupting the system of value. In this dimension, the principle of equivalence is no longer valid. In other words, the principle of equivalence of capitalistic exchange is constantly failing, its standard of value is disordered, and this failure and disorder is always in progress. What is happening is a proliferation and acceleration of exchange, the deviation from exchange, and the deterritorialization of exchange. Arthur Rimbaud wrote a poem about the buying and selling of new bodies, which would disrupt the market.[*19] (Also, Rimbaud discarded poetry and became a merchant.) Nijinsky wrote about “lawsuits” with Diaghilev over money. He repeatedly wrote in The Diary that he wanted to go to a stock market, make a fortune with stocks, destroy the market, and bestow limitless wealth to the poor. It seems like a fantasy surrounding God, love, and the destruction of exchange value was at the center of Nijinsky’s conflict.

However, we need to differentiate God from dance. Nijinsky writes, “My habits are different from Christ’s. He liked sitting. I like dancing.”[*20] Exchange is inherently unequal, unbalanced, and unjust. Nijinsky’s dance stands and lies in the middle of revealing that unjustness and destroying exchange through exchange, where another dance springs out. Amid the struggle of the madness of exchange and the exchange of madness, Nijinski à minuit unfolds.

Note

- 1.Nijinsky, Vaslav. Nijinski no Syuki. Translated by Sho Suzuki, Shinshokan, 1998, p.80.

- 2.Nijinsky, Vaslav. The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky. Edited by Joan Acocella, University of Illinois Press, 2006, p.32

- 3.Nijinsky, Vaslav. Nijinski no Syuki. Translated by Sho Suzuki, Shinshokan, 1998, p.80.

- 4.Nijinsky, Vaslav. The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky. Edited by Joan Acocella, University of Illinois Press, 2006, p.67

- 5.Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Vol.3: The Care of the Self. Pantheon, 1978, p.57

- 6.Nijinsky, Vaslav. The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky. Edited by Joan Acocella, University of Illinois Press, 2006, pp.14-15, 28, 108, 151, 221.

- 7.Murobushi, Diary of Ko. Murobushi, 2014.

- 8.Suzuki, Sho. Nijinski Kami no Doke. Shinshokan, 1998, p.93.

- 9.Ibid., pp.142-143.

- 10.Ibid., p.194.

- 11.Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. Anti-Oedipus: Captialism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press, 1983, p.77.

- 12.Nijinsky, Vaslav. The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky. Edited by Joan Acocella, University of Illinois Press, 2006, p.44.

- 13.Ibid., p.75.

- 14.Ibid., p.54.

- 15.Ibid., p.103.

- 16.Ibid., p.104.

- 17.Marx, Karl, and Fredrick Engles. The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1884 and the Communist Manifesto. Translated by Martin Milligan, 1st ed., Prometheus Books, 1988, p.71. This sentence was referenced in Jacques Derrida’s theory on Antonin Artaud.

- 18.Klossowski, Pierre. Living Currency. Edited by Daniel W. Smith et al., Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- 19.Rimbaud, Arthur. Illuminations: Prose Poems. Translated by Louise Varèse, New Directions, 1957, p.146. From the poem “Sale.”

- 20.Nijinsky, Vaslav. The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky. Edited by Joan Acocella, University of Illinois Press, 2006, p.23.

Kuniichi Uno

He was born in Matsue city in 1948. He is a French literary critic and the former professor at Rikkyo University’s Department of Image and Body Science. He continues to write essays focusing on body theory and body philosophy. He is the author of Artaud: Thought and Body (Hakusuisha), Theory of Body Image (Misuzu Shobo), Political Reflection (Seidosha)、and translated F. Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus, A. Artaud’s Pour en finir avec le jugement de Dieu (Kawade Bunko), G. Deleuze’s Foucault, Le Pli, S. Beckett’s Molloy, Malone Meurt, L’Innommable (Kawade Shobo Shinsha), and more.